Godless (2017) is a great show. I loved it, and seeing it has restored some of my confidence in Netflix's ability to churn out worthwhile original content. I'll talk about it in a moment. First, I have to get something off my chest...

I've had issues with Netflix, recently. Ever since June (or thereabouts) of this year, I've lost interest in the streaming giant, given their baffling change from a 5-star rating system, to a simpler binary one, where viewers merely provide a thumbs-up or thumbs-down. Granted, I wouldn't have minded much, if it worked; point in fact, it doesn't. Given that they also took away the "highest-rated" feature, all this "spring cleaning" seems like a naked, calculated way to try and disguise the shortcomings of their own "original" content. Alas, said output seems to consist largely of Marvel miniseries—some good, some not—and poorly-reviewed stand-up comedy sessions, like Amy Schumer's; or terrible Adam Sandler vehicles. Meanwhile, much of the rest seems to have actually been outsourced, borrowed from other companies, such as with the excellent miniseries, Manhunt: Unabomber (2017). This show was actually produced and aired on Discovery, this August; it wasn't purchased by Netflix until November. Yet, on Netflix's site, it is advertised rather misleadingly as a "Netflix Original." It most certainly is not; they merely purchased the rights to it.

More power to them, I suppose. Certainly purchasing the rights to other films and intellectual property helps one get around the issue of having to repurchase rights to display content that someone else owns. That's why many films come and go insofar as being available on Netflix's online catalogue; those that were available years ago are no longer, and when they are, they remain so only for a period of months. It's cheaper and simpler to purchase the rights of the product outright, or make it oneself. However, as already mentioned, much of the output Netflix makes has been sub-par, a fact crudely disguised by a complete revamp of their rating system. They'd probably refer to it as "streamlining." In fact, as their rates continue to rise (which may have something to do with Net Neutrality being on the chopping block, in the United States) they argue for these price climbs by saying they are continually dedicated to "improving" the Netflix viewer experience (so their automated e-mail insisted, anyways). In my opinion, they've done nothing but contribute to its steady and swift decline.

I'm left, as of now, feeling a strong thirst for original content that makes me want to renew my subscription. After all, there are plenty of alternatives—Starz, Amazon, Hulu. They might not be any better, overall, but the fact of the matter is, they have plenty of original content that continues to fare critically well, without being prostituted exclusively to neighboring websites in dire need of a flagship series. By and large, this seems to be is the best Netflix can seem to do: borrow from others. Their own various Marvel miniseries have been hit-or-miss. Jessica Jones (2015) was grand; Daredevil (2015) and Luke Cage (2016) were decent; Iron Fist (2017) was a huge let-down; and frankly The Defenders (2017) wasn't much better. Apart from Stranger Things 1 (2016) and 2 (2017), it's only until The Punisher (2017) came along that I felt a jolt life run throughout an entire miniseries—something produced in-house that wasn't borrowed from somewhere else, like Manhunt: Unabomber was, or Black Mirror (which originally aired on Britain's Chanel 4 in 2011, and wasn't purchased by Netflix until 2015).

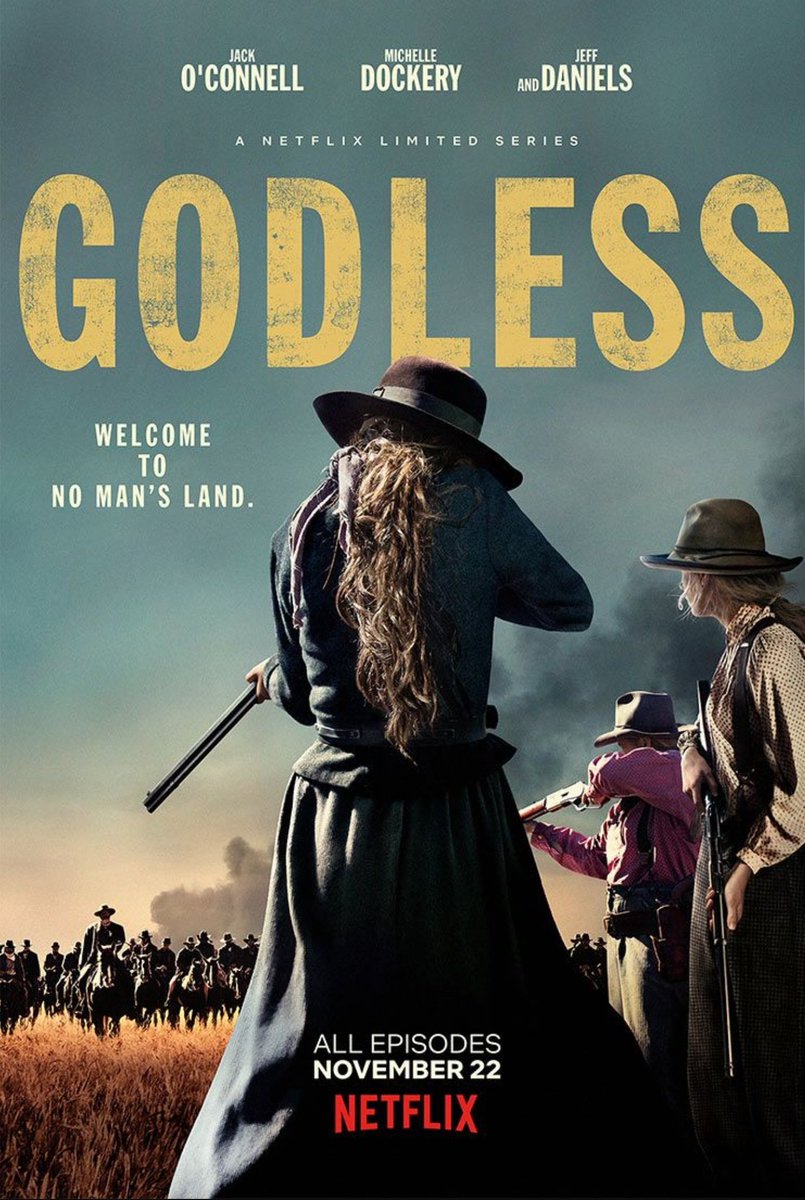

I'll reserve talking about The Punisher and Stranger Things until a later date (and I still need to sit down and watch Mindhunter [2017] too). For now, I'd like to discuss Netflix's actually-original miniseries, Godless. To be clear, this isn't a show bought off of someone else (not that there's anything wrong with this, by itself; there is, however, when you want your own content to keep customers coming back for more original fare). This is a show made by them that a) isn't attached to Marvel, b) doesn't serve as a lucrative comedian's shoddy vehicle, or c) isn't Stranger Things.

And the show is great, I might add. Did I mention that, already? Well, let me say it, again: Godless (mostly) rocks.

And having recently been exposed to a number of classic Westerns (of the Sergio Leone variety), as well as being well-acquainted already with a number of others, old and new—Open Range (2003), Unforgiven (1992), The Wild Bunch (1969), The Duelists (1977), Seven Samurai (1954), Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)—I feel safe in saying that I have plenty of movies to compare it to and favorably so. Like those films, this show brings something memorable to a table that is well-visited, and overpopulated by a legion of poorly-made outings that do little to discourage the overbearing notion that the Western is dead and buried.

Granted, most movies borrow on older oral traditions that have remained by-and-large unchanged, structure-wise, for thousands of years. The visual medium, along with the oral traditions that preceded it, are fairly constant, in that regard. But it's so very easy to get these tried-and-true formulas wrong—in any genre, not just Westerns. And yet when a new Western comes out, I am often dubious, until I am happily proven wrong by the likes of a would-be has-been like Kevin Costner or George Miller. Both Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and Open Range are fabulous.

So what's so great about Godless? Why does it deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as those films? Well, to be clear, it almost can't—not unless one overlooks the fact that one is a miniseries of seven one-hour long (or thereabout) episodes, and the other two are feature-length films; it's a case of big screen versus little screen. There are limitations to any comparison, given that one medium allows for certain possibilities, and another doesn't. Likewise, there are certain inherent disadvantages contained in each mode. But the spirit of the Western is alive in both: the evocation of mood and scene; the well-established tropes of the wandering, nameless hero; the widow with the Winchester rifle contending with hostile natives in uncharted territories; commentaries on society before, during and after the Civil War; etc.

What works in a movie needn't work in a miniseries, and vice versa. That being said, what's shown in Godless largely works handsomely—for the most part. I'll save delving into its flaws for another article. In the meantime, one or two gaffs aside, this is a fine show that fires on all cylinders. Just don't except those cylinders to be of the revolver variety and you'll be in for quite the treat. By that I mean that the weakest element of the show is actually the much-touted and foreshadowed showdown in the town of La Belle, itself. Virtually everything leading up to this is delivered with such vivid, emotional detail, that the battle itself, as violent and shocking as it tries to be, merely comes off as something of an afterthought.

I certainly don't mind gun battles. One of my favorites is immortalized by Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch, a film that, to this today, in my opinion, has yet to be outdone, in that regard. In Godless, however, whatever heft its own battle would have had is undercut somewhat by just how effective the rest of the show is, as well as by some writing and technical snags (which, again, I'll explain, in another article). It's almost like they didn't even need the battle, and a part of me wishes they'd have left it out, because it honestly doesn't hold a candle to how wonderfully-shot the rest of the show is. Each episode is composed of lengthy scenes, introduced in deliberate, loving fashion, wonderfully photographed, and framed with utmost care—so much so that I watched the Kieran Darcy-Smith Western, The Duel (2016) afterward, and found that film, as handsomely as it appeared, to be somewhat plain.

Not only is Godless gorgeous, but the music was, for a change, something other than the typical, singular pounding of orchestral percussion (think: Hans Zimmer) that plagues so many movies and shows, nowadays. I remember films like Conan the Barbarian (1982) and Star Wars (1977) and look to the past with a sense of untold longing. Likewise, the Western, in its heyday, was known as a reliable source for excellent music (think: Ennio Morricone). Films like Open Range emulated with aplomb this past confidence in narrative-driving musical scores. So, too, does Godless, a miniseries with actual melodies (!)—not just leitmotifs, but classical underpinnings that I could recognize as the music played, in front of me. It felt so refreshing to hear that, in any kind of media, these days. Furthermore, this refreshment was doubled by how the music, itself, complemented the scenes perfectly. No tune felt out of place; much of the accompaniment was poignant, evocative of the events unfurling onscreen dramatically the way that music should. In other words, like the music with many-a-classic Western, Godless' upholds the same immortal tradition of using music to convey mood. Kudos, Carlos Rafael Rivera; you knocked it out of the park.

From a writing standpoint, the characters themselves were all enjoyable in the sense that very few of them actually got along—at first. For one, Mary and the widows have it out for Alice. Yet, eventually the two diametrically-opposed matriarchs fight side-by-side, united against a common threat in a way that doesn't feel (too) forced. We also see O'Connell's gradual evolution from Roy Goode to Mr. Ward, a metamorphosis that takes the entire miniseries to culminate, and when it does, it is perhaps expected, but more or less satisfying. It ends much in the same manner as many Westerns have in the past—with John Wayne riding off into the sunset with Grace Kelley ("That's Gary Cooper, asshole."). Goode is the male protagonist, here, to be sure, but given that this show is one invested in the fate of a town of widows, it should hardly come as a surprise that his time on the stage is shared with them. A number of the widows (and their associates) are memorable. Fully-fleshed out characters like Whitey Winn, Bill McNue, and Mary Agnes all get plenty of time in the spotlight, with very little of it feeling obligatory. The widows from La Belle bicker with Alice Fletcher and themselves, and between the interwoven lot is just the right amount of exposition without making the whole affair feel bogged down. It entertains, but remembers to keep moving.

There is also the villain, himself, played with a curious mixture of loathing and sympathy by Jeff Daniels. Here, he's playing against character for a change—the exception being Eastwood's Bloodwork (2002). In fact, Daniels more often than not plays "good" ornery characters, or mentally-disturbed ones, often for laughs, but also seriously. Here, as a villain, it also works; and yet, I see him reaching into the same bag of tricks that he used to play Lewis, a blind man in Scott Frank's The Lookout (2007). When I see Daniels, as Frank, bemoaning the fate he didn't see coming right before Roy shoots him in the head, it's for me hard not to see Lewis, blindly asking whether or not he's dead, after Joseph Gordon-Levitt's character, Chris, shotguns that movie's villain.

Such is the lot of a man with a career as extensive as Daniels'. He doesn't do a poor job—he's competent. It's just that I'm not really a fan of his work, overall. I can appreciate his talent, but generally find most of his roles boring. He generally plays it straight, and when he doesn't, he's not as magnetic as I'd like. Vice characters should be seductive, or entertaining. While he comes off as educated, Daniels' Frank is neither of those things, for the most part. That being said, he functions as more of a story-telling device, anyways—the linchpin for a revenge mechanic that would not be entirely out of place in some of the other films I've already mentioned, thus far.

A Western generally needs a villain with a posse. Daniel's Frank Griffin proves that such a character need not be the most interesting part of the show for the formula to work. To his credit he works consistently to make Frank a more interesting villain than the role requires. He's not always successful, as the added qualities don't really make him a more effective villain. In other words, he's not quite as enjoyable as James Earl Jones' Thulsa Doom, in Conan the Barbarian. He's more like Henry Fonda's Frank, in Once Upon a Time in the West (1968). He just seems confused or lost when he meets his end.

Daniels' villain is also mistakenly topless, for the final duel. The duel, itself, is shot well, and scored nicely, but Daniel's wrinkled dugs—much like T.S. Eliot's "Tiresias, [the] old man with wrinkled dugs" in The Wasteland (1922)—prove to be quite the eyesore. I suppose they were playing at his geriatric insanity by showing him disrobed, vulnerable (and like the Emperor, with his proverbial new clothes). I just didn't think they needed to. The image of his unsightly body was frankly distracting more than anything else. All this being said, Daniel's villain is much better than Michel Gambon's Denton Baxter. At the same time, Open Range didn't need Baxter to be interesting in order to provide the superior gun battle (which is ultimately what many Westerns, if not all of them, are all about).

This undoubtedly begs the question, why is Open Range's gun battle better than Godless's? For me, it boils down to writing and technical execution. On one hand, if the writing doesn't hold water, the action will feel pointless, or forced (not necessarily a bad thing if the visuals help you forget that, as is the case in many action films, Westerns or otherwise). On the other, if the visuals stink, you'll feel cheated out of a climax promised to you for the entire show. Make no mistake, Godless makes such promises in spades: As an audience, we're probably reminded of the impending disaster once every ten to fifteen minutes, in each episode; it's also the focus of the ad material, with Christiane Seidel's character, Martha, on display with a pistol sitting comfortably on each hip. Godless: Come for the gun battle; stay for the lush visuals, music, and diverse characters than make up most of the show.

The issue with Godless is it does admirably well up until the final battle, and then sort of drops the ball, getting both the visuals slightly wrong and the writing. To the show's merit, it recovers, following the siege's end, but by then, the show is nearly over, and has wasted several narrative opportunities.

One of them, in particular, really rubbed me the wrong way. In the next article, I shall describe this gaff in greater detail. Perhaps I'm making a big deal out of it. Perhaps not. Regardless, it feels glaring enough to me to merit a minor polemic. Before proceeding with said polemic, I need to be clear when I say that it does not mean I dislike the show. Point-in-fact, it's a great Western. In case I wasn't clear about that, I'll say it again: Godless is a great show and if you're a fan of nicely-shot and -acted Western, you owe it to yourself to watch it.

***

Persephone van der Waard is the author of the multi-volume, non-profit book series, Sex Positivity—its art director, sole invigilator, illustrator and primary editor (the other co-writer/co-editor being Bay Ryan). She has her independent PhD in Gothic poetics and ludo-Gothic BDSM (focusing on partially on Metroidvania), and is a MtF trans woman, anti-fascist, atheist/Satanist, poly/pan kinkster, erotic artist/pornographer and anarcho-Communist with two partners. Including her multiple playmates/friends and collaborators, Persephone and her eighteen muses work/play together on Sex Positivity and on her artwork at large as a sex-positive force. She sometimes writes reviews, Gothic analyses, and interviews for fun on her old blog; or does continual independent research on Metroidvania and speedrunning. If you're interested in her academic/activist work and larger portfolio, go to her About the Author page to learn more; if you're curious about illustrated or written commissions, please refer to her commissions page for more information.

Comments

Post a Comment